Nikita lives in Nizhny Novgorod, a central Russian city of one million inhabitants.

He wants to study in Moscow and in a few months he will find out if his grades are good enough.

"There's no prospect for me here," he says.

"A job in an office for 50,000 roubles (£633; $880) a month is the best I can hope for in this town."

After finishing school, many young Russians head to Moscow or St Petersburg. That is where the jobs and the money are.

Nikita's dream is to become an entertainer. He wants to be like Ivan Urgant, a Russian late-night talk show host similar to Stephen Colbert or Jimmy Kimmel.

"But you can't speak freely on TV," he says. And censorship is not the only problem.

"We live in a feudal state here in Russia," Nikita says. "If I look for a good position after graduation, all the nice posts will be taken by well-connected sons."

The idea of boycotting the "election with no choice" is Alexei Navalny's.

The opposition leader is barred from standing as a presidential candidate because of a corruption conviction that he says is politically motivated.

Navalny has been campaigning against corruption since 2008, but he became popular among teenagers in the spring of 2017.

Youngsters like Nikita turned out to Navalny's anti-corruption rallies all over the country, unafraid of the police who detained many protesters.

In March, when the rallies spread to 82 Russian cities, teachers and university professors started berating their students for attending the protests.

But the teachers proved out of touch with their digital-savvy students.

All over the country, pupils recorded teachers trying to humiliate them and uploaded the films on the internet.

'Putin has never done anything wrong to me'

Election after election, fewer and fewer voters go to the polling stations. Many want to rid their lives of politics altogether."I would be fine with a monarchy," Ivan Sourvillo shrugs. "I guess Stalin is not OK, but I can live with any government that doesn't touch me personally."

Eighteen-year-old Ivan has a successful blog. He interviews well-known Russians and writes about his travels and the lectures he has attended. With about 20,000 subscribers, he can make about $150 a month.

Ivan lives just off the Arbat, a prosperous part of central Moscow filled with souvenir shops and artists waiting for tourists.

Ivan lives just off the Arbat, a prosperous part of central Moscow filled with souvenir shops and artists waiting for tourists."Is this where you used to run around when you were younger?" I ask.

"I didn't run around, I read books," he answers earnestly.

Ivan was born in 1999, shortly before Vladimir Putin came to power. He can vote for the president, but he has not yet decided if he will.

"Putin has never done anything wrong to me - he does many right things," he says.

"He is definitely better than Trump, for example. Sure, the same people shouldn't rule forever. On the other hand, Russia's traditional form of government is monarchy."

'If not Putin, then who else?'

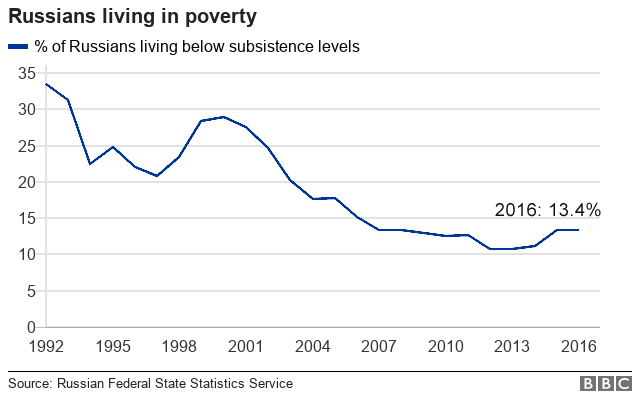

"You would walk out into the street and someone would steal your trainers from you," Alya Bazarova says of Russia in the 90s, a time before she was born."Putin practically restored the state. Compared to [former President Boris] Yeltsin, he was a reformer."

Alya, 18, is in her first year at a Moscow university. She calls herself a provincial girl - three years ago, her family moved to Moscow from Kursk, a city of fewer than 500,000 people.

"Everyone thinks it's impossible to live in the provinces," she says. "But I see Kursk developing. Shopping malls are being built. We even have traffic jams now - that means people are buying cars.

"And all this with a governor who has been there for, like, 20 years."

She sometimes discusses politics with her boyfriend.

"He says: 'Any government which is there for too long becomes bad'," Alya explains.

"And my dad says: 'If not Putin, then who else?"

When Alya was growing up, her family saw the same presidential candidates over and over, looking older every time. This time, things are slightly different.

The communists have put up the successful businessman and Stalinist Pavel Grudinin. And TV star Ksenia Sobchak is standing as a liberal opposition candidate. But Alya isn't convinced.

Alya has decided to vote on 18 March. But only out of curiosity - she has never been to a polling station before.

"I don't really believe in democracy," she says, lowering her voice a little.

"Everything is decided for us. Let's say the vote [has an unexpected outcome]. Don't you think they'll just swap the votes? Come on…"

Everyone in Russia knows who is going to be the next president. But they probably will not need to stuff the ballot boxes to win.

"Who are you going to vote for?" I ask.

She laughs awkwardly.

"Well, who can you vote for? All the candidates are chosen specially so it's obvious who you should pick."

No comments:

Post a Comment